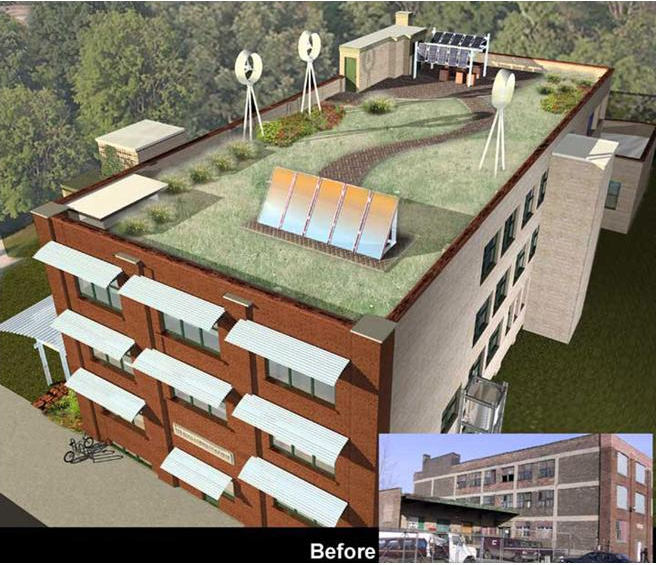

Bubbly (aka the Chicago Sustainable Manufacturing Center)

In 2002, Bubbly Dynamics acquired the former Lowe Brothers Paint warehouse, located on a largely abandoned block in the Central Manufacturing District; at the time, there was no public water service to the entire block. Bubbly Dynamics began renovation of this vacant building into an affordable, energy-efficient space for small and emerging manufacturers, product assemblers, and other businesses committed to sustainability.

By 2007, renovations of the 24,000 sq. ft. building were complete and had been achieved at a very low cost, achieved by strategic salvage and reuse of waste-stream materials, bartering with local suppliers, and working with volunteers. The building’s tenants, who range from furniture manufacturers to bike builders, have collaborated in ways that have grown their businesses, thus reinforcing the operational stability of the building as a whole.

Amenities include: Green Roof /Community space for exhibitions, seminars and events / Concrete floors / 3-Phase power / Large loading dock / DSL / Microprocessor controlled radiator heat / Showers

The following are tenants at Bubbly:

A Short History Of Bubbly

In 2001, the former paint warehouse at 1048 West 37th Street was known as the last resting place of the venerable Scooter World by motorcycle enthusiasts, and as Little Beirut by staff in the Chicago Planning Department. It was by all accounts a boarded up fortress of a building with a barricade of broken motorcycles and empty shipping containers out front, operated by scary guys with names like Cowboy and Googs, who were known to entertain themselves by exploding cardboard boxes filled with acetylene off the loading dock, shooting out windows of neighboring buildings for target practice and getting into mean, even murderous fights over small sums of money. At least it is said that Cowboy was sent back to prison for beating an old man to death for the cash in his pocket. And they say that turned out to be about $37.

All this made 2001 a colorful, transitional moment in the building's history, which stretches back to the turn of the last century, when Bridgeport was ascending as one of the most dense and diverse industrial districts in Chicago. In 2002, the old Lowe Paint Warehouse was acquired by Bubbly Dynamics LLC. Since then, it has been gradually reinvented as the Chicago Sustainable Manufacturing Center -- an incubator for emerging enterprise appropriate to a new industrial city.

Bridgeport, like Chicago in miniature, rose to prominence at a good spot on the nation's evolving transportation network. Chicago became the hub where raw materials collecting from the West were transmuted into manufactured products for the markets to the East. Bridgeport's industry also arrived in tandem with transport. In the early decades of the 19th century the cattlemen drove their herds up Archer Avenue; by 1848, the town was a port on the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and by 1857, it had its first railroad station west of Lock Street. By the 1880s, trains traveling to all corners of the United States stopped at stations in Bridgeport. Early trades catered to the canal and rail traffic itself -- feed dealers, blacksmiths, saddlemakers and coopers -- and then developed around the raw grain, lumber, cattle, coal and iron they carried.

In 1865 the Union Rolling Mills opened their steel plant near Ashland Ave and 31st Street, by the South Fork of the Chicago River, in the same year that the Chicago Union Stockyards opened its district in the neighborhood south of Pershing Road. Initially, the stockyards were mainly a livestock exchange. Associated industries -- the packinghouses, tanneries and glueworks -- spilled up into Bridgeport. There was similar spillover from the lumberyards. The Great Lumber District lay primarily on the opposite side of the river from Bridgeport, between Halsted and Ashland. But once the district grew crowded, lumber, shingle and lathe spread down the South Fork of the River.

The stock and lumberyards were laced with rail spurs connecting to the major trunk railways and on to markets across the nation. Many of those spurs had been laid by the Union Stockyard and Transit Company. In 1890, the Stockyards were sold, and the rail company was run as a separate business by an East Coast investor named Frederick Henry Prince under the name Chicago Junction Railway. Having absorbed the stockyard traffic, the Junction Railway expanded into the lumberyards. By end of century, the Wisconsin woods were waning, the lumberyards were in decline, the stockyards had already begun looking toward more spacious parts of the Midwest (though they would not completely shut down in Chicago until 1971) and Prince struck a new scheme for generating freight traffic for his railroad.

In 1905, he created the Central Manufacturing District. Often described as the nation's first planned industrial district, the CMD took the concept of corporate districting tried in the stockyard and lumber districts to new levels of coordination and planning: The CMD built its own infrastructure of rail and street access, water, lighting and power. Firms locating there could build their own plants, or they could rent modern facilities from the CMD. Either way the CMD had also created an institutional infrastructure to back them up. There was a CMD bank, that could finance their start-up costs; there was a staff architect and engineers, who kept abreast of the most modern innovations in industrial construction; there was an executive's club, housed in the bank building, where new businesses could benefit from a network of their peers like those that established firms enjoyed at downtown institutions.

Historians emphasize the incubator function of the CMD. It was particularly attractive to new businesses, or businesses from out of town wanting to test a Chicago location. It offered the amenities of a central city location without the barriers posed by the crowded, older sections of downtown where industry competed for space with other sectors. The CMD had 256 acres of space between Morgan St and Ashland Avenue, from 35th St south to 39th, or Pershing Road. Its buildings were new and modern.

The Bubbly Dynamics building at 1048 West 37th Street, in the district's eastern quarter, provides a fine example of the period's best industrial design. Built in 1910, it combines the compact, 3 story footprint and abundant natural light and ventilation of the old mill structures with a new reinforced masonry construction, in place of the timber frame of older buildings. Within 20 years the newest industrial buildings would be built as sprawling single story structures where materials could be moved from one end to the other without entering a stairwell or running an elevator. But the older, compact style lent itself to the CMD's incubator function. New firms looking for a foothold were eager to lease smaller units on a floor of a shared building, in a district segregated from residential uses, but close enough to other firms that synergies could flourish.

By 1915, the CMD was host to about 200 businesses, employing almost 40,000 people in combination with the Stockyards just south of Pershing Road. By 1951, there were 101 firms in the CMD including 69 in manufacturing, 23 in storage, 2 in transport and 7 in heavy service. Between them they employed about 11,500 workers. The Stockyards employed more -- about 32,000 workers -- but the CMD supported the same number of firms (there were 104 businesses in the Stockyards, 101 in the CMD).

These were peak years for industrial employment near Bridgeport. By the late 1950s, the demand for vast, single story facilities along interstate highways outside of town had started to take its toll on the CMD, and on Chicago industry in general. Traditional industry moved out from the central city over the next 40 years. And as it did, the informal economy moved in.

In the late 1960s, a young man named Bob Krueger opened a little shop called Scooter World south of the old stockyard district. There was a motor scooter craze at the time. He'd pull abandoned machines out of the trash, he'd rebuild them or sell parts. He dealt in motorcycles too, in fact, anything with wheels or an engine -- lawnmowers for instance. Over the next years he'd operate from half a dozen locations on the south side. By the late 1980s he was in the former Lowe Paint Warehouse on 37th Street in the old CMD. A man named Brown owned the building; Krueger had it crammed from the basement to the roof with motorcycles and parts. The basement was filled with wheels of all kinds; there were engines stung like hams from the I-beams in the loading dock. Scooter World was known across northern Illinois, maybe further than that.

But then Brown died and his daughter inherited the building. Her boyfriend, Cowboy moved in. Cowboy and his girlfriend let the building deteriorate. The utilities, once a proud feature of the district, were cut off and they'd burn trash in barrels for heat. Krueger, who was sometimes known as Santa as he got older, lost control of the business he built by knowing what things were worth. Not just motorcycles either, scrap metals and odd parts. He once sold 20 car axels to a traveling circus, which used them to stake down the tents. Cowboy didn't know what anything was worth, or didn't care. He'd sell something that was worth $50 for $5 if he could have the cash right away. By 1998 Brown's daughter had lost the building for back taxes at a scavenger sale. The new owner let Cowboy and Scooter World stay on. But within a few years he was ready to sell.

In 2002, the building at 1048 West 37th Street was purchased by John Edel through a company named Bubbly Dynamics LLC in honor of the old Bubbly Creek, which is what the South Fork of the Chicago River's South Branch had come to be called when it used to boil with decaying waste from the Stockyards. Edel studied industrial design at UIC and made his living working in Chicago's high tech industries. For 10 years he built virtual sets for the post-production house Post Effects. But he maintained an interest in concrete technologies too, in industrial heritage and railroads. He chose the old Lowe Paint Warehouse in part because it had rail access, and mid level managers at Norfolk Southern were willing to restore the service. Though higher level managers put that plan down, at least for now.

Edel saw the building as an opportunity to try new building techniques, designing efficient spaces himself, and trying new and sustainable technologies as he has built the space out for boutique manufacturing that is resurging in the central city. Renamed the Chicago Sustainable Manufacturing Center but still simply known as “Bubbly,” the building itself was saved from the landfill, even as buildings like it are razed every year. In fact, many of the materials used to rebuild it have been pulled from the waste stream. Bob Krueger has continued to come by to check out the building's progress. He has also been a regular source of useable materials, and has carted away tons of scrap to his network of interested buyers. A hundred years ago, the former paint warehouse was built to maximize natural light and ventilation. Its reinforced masonry structure was built to be fireproof, virtually indestructible. And these features continue to serve in the building's new incarnation as an incubator for small and emerging business.

Courtesy of Kristin Ostberg